by Kim Kennedy | Jun 23, 2020 | Latest News

Image: Source PHYS ORG https://phys.org/news/2017-10-pursue-low-cost-efficient-technologies-hydrogen.html

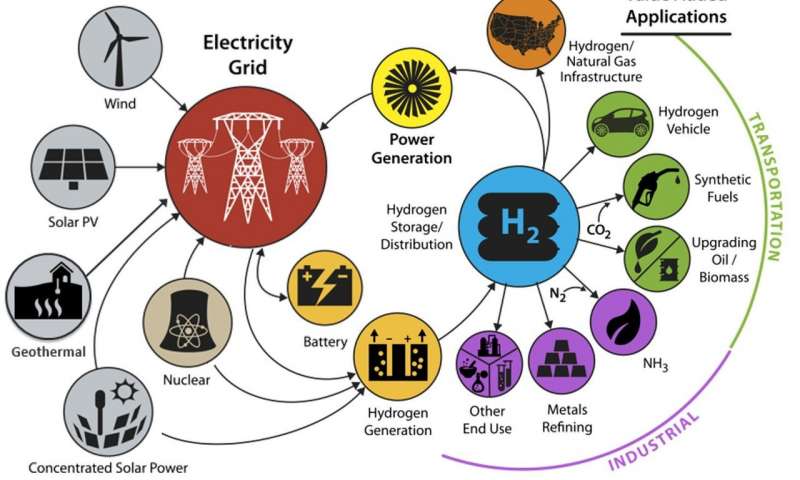

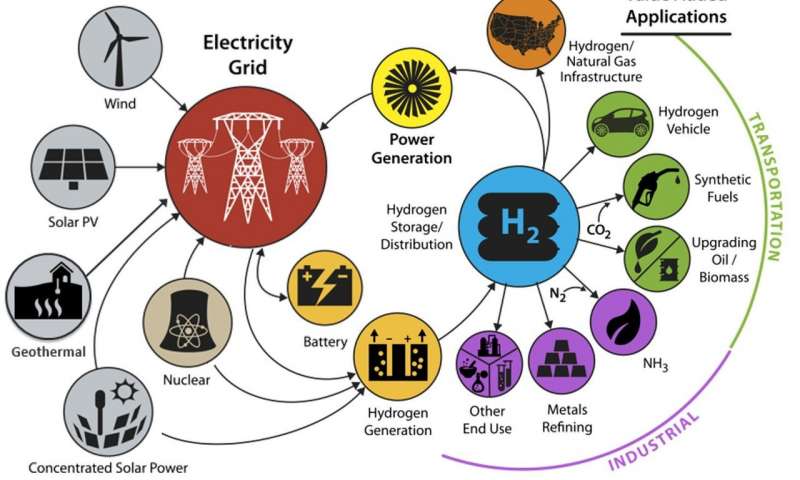

The Government’s Technology Investment Roadmap – discussion paper invited industry and the general-public to consider which sustainable technology Australia should invest and develop. The Roadmap is the latest approach to decarbonising Australian industry, transport and agricultural sectors and it looks like the Government is backing Hydrogen technology as a winner.

There is a growing global appetite to explore hydrogen as a form of renewable energy. Industry is making the technology breakthroughs necessary to reduce the cost of generating hydrogen and countries like Japan, South Korea, Germany, and the US have been investing in hydrogen technology as the pathway forward over the past decade or more.

Hydrogen presents a viable alternative to conventional fossil fuels in Australia and conditions are now favourable to capitalise on international technology breakthroughs and grow both hydrogen domestic and export markets. Large scale production is yet to be realised, but it is only a matter of time. Establishing a new value chain in a mature fossil fuel-based market is attracting new ways of building industry ecosystems.

H2SEQ is an industry-led Hydrogen Industry Cluster focused on sustainably growing the Hydrogen industry ecosystem in Greater Brisbane/South East Queensland region. The Cluster joins industry bodies, research institutions, businesses, large companies, and specialist services that contribute to the value chain. H2SEQ participants are exploring opportunities to engage end users in the process and develop a viable hydrogen industry in Australia.

The export market currently in negotiation with Japan and South Korea will hopefully pave the way for a domestic transition to hydrogen in Australia. It is vitally important to create a value chain in Australia for the hydrogen industry to gain a foothold and build towards an export market. Australia’s competitive advantage is our skills in gas extraction, use, and export; the availability of land to develop on, and complimentary minerals i.e. Iron ore to build a hydrogen industry around. We will need to carefully select existing hydrogen technology to suit the Australian climate. Whilst TRI/CRL scale is an essential consideration for investment selection, it should not be the only focus. At a macro and regional level, the cost, business impact, value across the life cycle, resource availability, execution effort and alignment to the technology priorities need to be considered. The maturity of the energy value chain and supporting infrastructure may not be ready yet and government will need to foster and plan for the sectors growth.

Australia’s competitive advantage is our skills in gas extraction, use and export; the availability of land to develop on, and complimentary industries i.e. mining, to build a hydrogen industry around. Transitioning industry and developing new job opportunities for displaced workforce is a challenge. The Grattan Institute green steel proposal has potential to achieve this goal and no doubt there will be many more proposals as momentum builds.

The Government’s Technology Roadmap indicates Australia is open for opportunities in hydrogen industry development. The Government should actively building Australia’s profile as a producer, trading partner and research partner in hydrogen. Attracting international research funding and expertise to Australia.

Following the release of the final policy later in the year Dr Alan Finkel and the Government intend to provide an annual report on the outcomes. The targets and KPIs that will form the annual reporting process will provide the blueprint for future investment. Hopefully, these will include emission targets, metrics around transitioning industrial feedstock, and targets for hydrogen fuel mixing with gas for domestic heating and cooking.

You can read the full QTLC & H2SEQ submission here

by Kim Kennedy | Feb 18, 2020 | Latest News

Crumbling institutions, lack of trust and unease about our future were the key themes of CEDA 2020 Economic and Political Overview in Brisbane #EPO2020. This year the normally quiet and lazy summer holidays were ablaze with bushfires, climate politics polarised Twitter and our political leaders were caught up in scandal and unethical behaviour. The Government might be saying all is well, a surplus is in the bag, but to the average person, it doesn’t feel like it is all going to be ok.

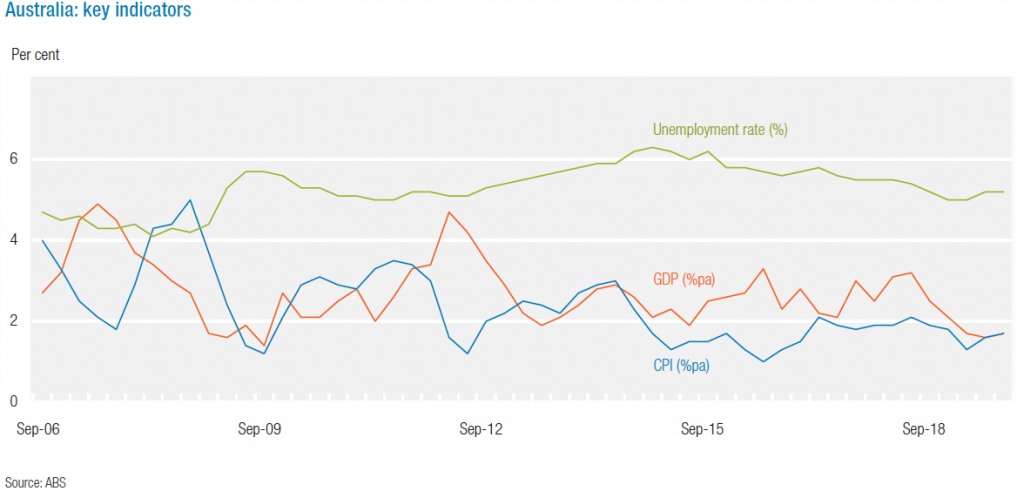

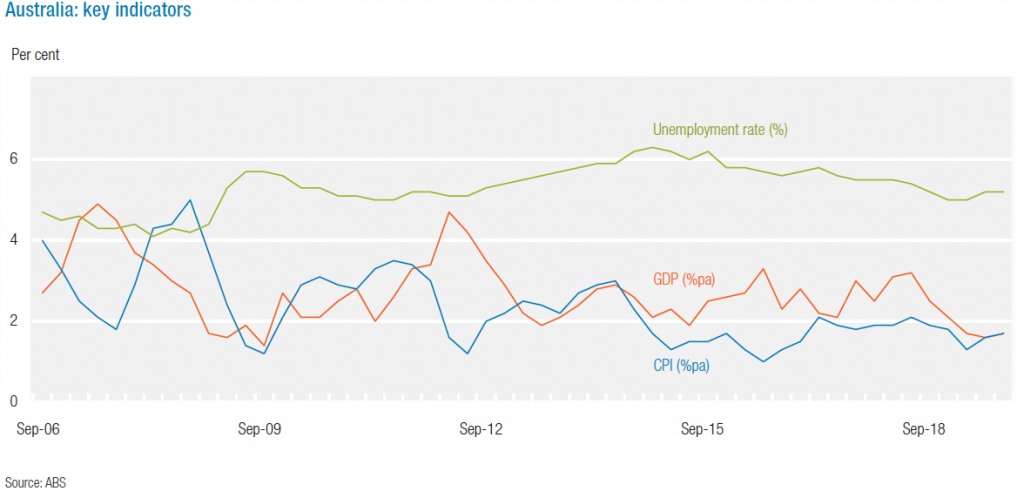

Michael Blythe Chief Economist and Managing Director, Commonwealth Bank opened the event and illustrated why Australian’s are feeling uncertain about the future.

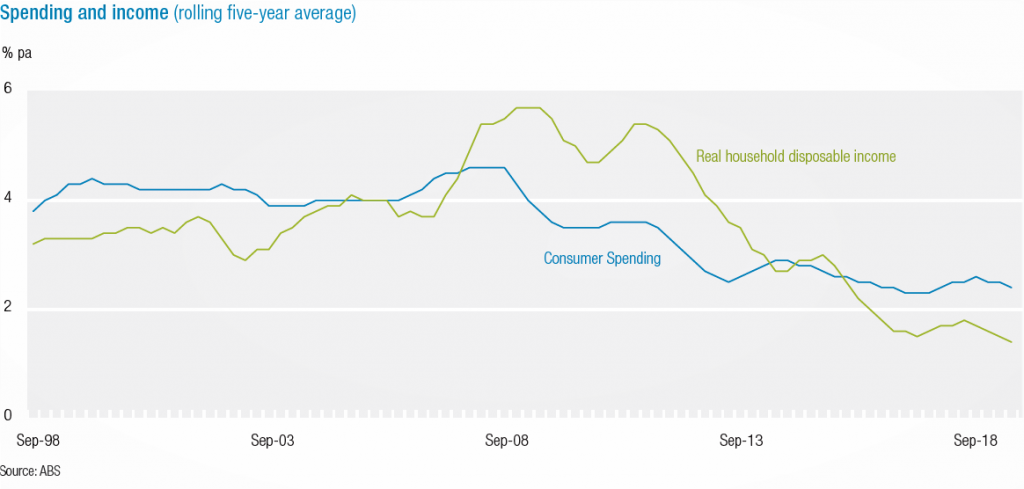

Australia has been riding a long wave of economic prosperity, low unemployment and stability. This prosperity has driven up the cost of living, precipitated a housing boom, casualisation of the workforce and stagnant wage growth. We may not be in a recession yet but the average ‘quiet-Australian’ is uncertain about the future.

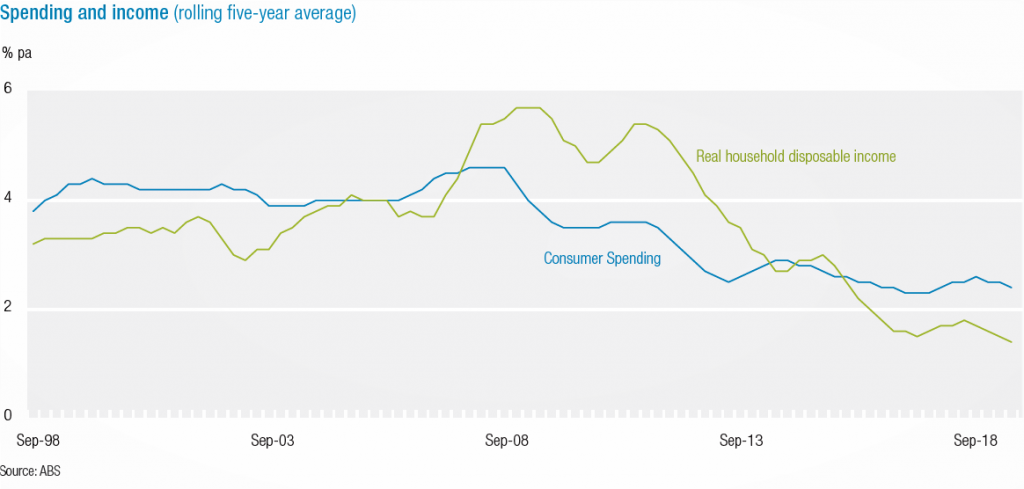

Domestic consumption is an important indicator it represents 56 percent of Australian GDP (see graph above). When we stay home and save money this impacts our bottom line. Globally, growth is also slowing, Coronavirus is adding strain to already troubled trade policy and climate change is disrupting traditional industries.

Trust Indicators

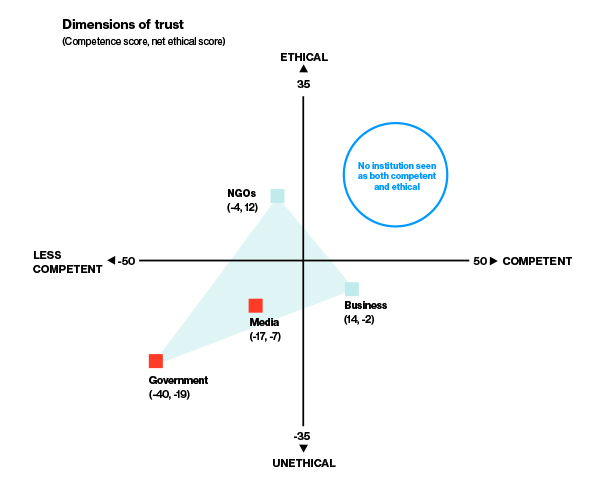

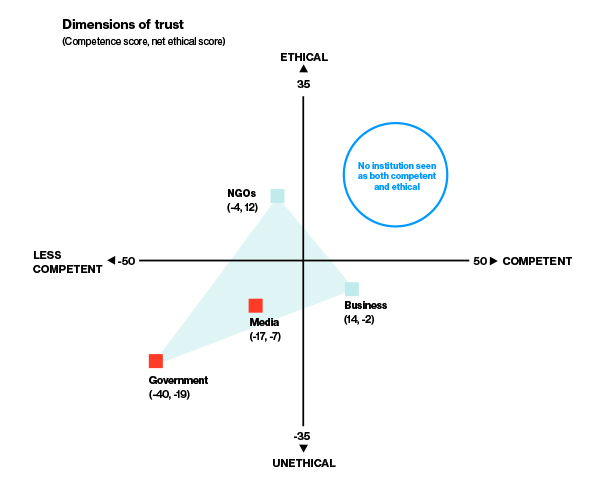

For me, the graph pictured above illustrates the disillusion I felt at the start of this year. Uncertainty about Australia’s economy, the lack of leadership or ethics as displayed by the Sports rorts affair, the increasing influence of big business in policy setting, the nastiness on Twitter, all contributed to my loss of trust.

The Edelman presentation at CEDA on trust indicators generated a great deal of debate striking a chord with most in attendance. Edelman 2020 Trust Barometer survey found that despite a strong global economy and near full employment, none of the four societal institutions that the study measures—government, business, NGOs and media—is trusted. Australians are amongst the most cynical in the group of developed nations and China was far more trusting of their institutions than Australia. The survey found people would like to see increased collaboration and bipartisanship, stronger leadership, and more transparent and ethical behaviour displayed across all institutions.

People base their trust on competence (delivering on promises) and ethical behaviour (doing the right thing, social license). Edelman global surveys found Australians are more confident about our business leader’s ability to be efficient and relatively trustworthy than our government. Business leaders are increasingly stepping over a line and into the policy space. A recent example of this is BHP’s announcement that it will aim for carbon neutrality by 2050, at a time when political leaders seem to be incapable of charting a clear policy direction. For many, this is an erosion of our democratic process and for others it represents the market rising to the challenge and driving change.

Peter Van Onselen warned that while Australia might be comfortable in our sleepy backwater, we should be conscious of the changing global tide. Democracy will face many new challenges over the next decade and we should not be complacent about its importance to our society.

Think global act local

For all the pessimism there was also plenty of optimism. We are not in recession, there is plenty of scope for innovation and Australian’s are inherently cynical of the status quo. Chaos at the macro level can be tempered at the micro. Build trust with your team, behave ethically and continue to deliver to your community. Consider delivering smaller scale projects with local governments while the large scale infrastructure boom is consuming the available pool of skilled Australian’s. Local governments are calling out for services, bridges, potholes, and buildings all need to be fixed. In America, novel approaches to building brand equity and social license are being trialed. Have a look at Domino Pizza’s ‘Paving for Pizza’ a great piece of brand building https://www.pavingforpizza.com/ Closer to home the CEO Sleepout is a good example building trust and understanding at the community level https://ab.co/2P0JxMf

Reference

Graphs sourced from CEDA 2020 Economic Outlook file:///C:/Users/61433/Desktop/CEDA-EPO-2020-Final.pdf

and

Edelman 2020 Trust Barometer https://www.edelman.com/trustbarometer

by Kim Kennedy | Dec 19, 2019 | Latest News, Road News

Australia faces profound challenges in managing and expanding its transport infrastructure network. Demand for passenger and freight transport will double over the next 25 year and triple by 2050. Inefficient and congested freight networks have a direct impact on productivity. Deloitte’s Economics estimates a one per cent annual improvement in supply chain efficiency will save Australia more than $1.5 billion in deadweight logistics costs.

The road charging and spending mix between the three levels of government federal, state and local government is very complicated. Revenue is collected through tax, duties, tolls, parking fees and levies. This revenue is declining and is not directly correlated to road spending. Changing the costs for the heavy vehicle industry is always the first step for government.

Following the Transport and Infrastructure Council announcement of a 2.5 percent increase in Road User Charges Mr McCormack’s office said the logical first step for road-user charging was the heavy vehicle sector.

Should heavy vehicles pay only for what they use? And if so, is mass distance charging inevitable?

Looking globally Australia has a similar situation to many other developed nations. All are facing declining revenue and increasing costs.

Michael de Percy explains in Road Pricing and Provision chapter 2 – Where are we and how did we get here?

At the heart of the public policy problem is the entrenched perception of roads as a free public good for which users do not need to pay (despite roads not being wholly a ‘public good’ in definitional terms; one person’s enjoyment of the good can impact on another’s enjoyment through congestion). Users see roads and their usage of them more or less as an inalienable ‘right’, and itemised payments for the use of roads through tolls and charges as an annoying infringement of these same rights.

New Zealand

New Zealand potentially has a more equitable system than Australia. Anyone using the roads directly contributes to their upkeep through either fuel or road user charges. New Zealand is unique in that the revenue collected is dedicated to the National Land Transport Fund which directly funds road improvements and maintenance. Rail revenue and expenditure is also funnelled through the Fund delivering a more holistic funding approach to freight. This enables the Government to consider the balance between road and rail and aim for a zero emission target by 2050.

Perhaps our New Zealand neighbours have a more transparent system, one that merits consideration? Deloitte’s certainly agrees suggesting nationalising and simplifying the Australian system and establishing a ‘Building Australia Fund’ to allocate resources to the states and territories is a good idea.

Australia

In Australia, revenue collection is split between the states (stamp duty, licensing and registration fees) and the federal government (Road user Charge – fuel excise tax, FBT, and GST). The formal funding framework between the Australian Government, the states and territories is defined in the National Partnership Agreement on Land Transport Infrastructure Projects. This intergovernmental arrangement sets outcomes around innovative network-wide planning for land transport; the connectivity of regional communities; safety, and productivity and growth. Each State then individually negotiates a funding arrangement under the National Land Transport Act 2014.

In total the Australian governments raise approximately $30 billion in road-related revenues and spend about $25 billion on road-related funding[1].

Figure 1 Road related revenue by type BITRE (2016)

Source: Road pricing and road provision in Australia: Where are we and how did we get here? Michael de Percy

The federal government applies a national heavy vehicle Road User Charge of 25.8 cents to each litre of diesel used by heavy vehicles as set out in the Fuel Tax Act 2006. RUC is designed to recover the heavy vehicle share of road expenditure through a complicated fuel tax credit system. Claiming fuel tax credits is up to the individual operator and many are averaging their use and only partially claiming the full amount.

Road User Charges were frozen in 2014 however, this freeze has recently been revoked and a 2.5 per cent increase is expected in 2020-21 and a further 2.5 per cent increase in 2021-22.

Gary Mahon, Queensland Trucking Association said the initial proposal of an 11.4 per cent increase was completely unreasonable.

“When you’re looking at companies on margins of about 4c in the dollar, an increase like this could well send a number of businesses to the wall,” he said

The government decision to not chase the full funding gap was mainly due to the united effort of state and national industry association placing pressure on the Government.

So how large is the gap in funding?

The Government is keenly aware that the amount of fuel excise tax collected has been steadily declining since the beginning of the 2000s (see figure 1). This is primarily due to technology advances, improved logistics management, increased vehicle efficiencies, and the growth in the electric vehicle market. According to the Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Development, in 2013–14, public sector road-related revenue totalled $27.8 billion. Fuel excise contributed about $10.8 billion or 39 per cent, down from about 44 per cent in the early 2000s.

Figure 2 Public sector spending BITRE (2016)

Source: Road pricing and road provision in Australia: Where are we and how did we get here? Michael de Percy

Australian Government’s infrastructure spending has increased over time (see figure 2). The recent stimulus packages offered to boost the stalling economy for example the recent $1.9 billion stimulus offered to Queensland add to the costs.

Why change may be needed?

John Wanna Road Pricing and Provision (Chapter 10) suggests there are five key issues with the existing array of pricing and cost-recovery mechanisms:

- They are indirect, unnecessarily complicated and politically messy, involving multiple but separate jurisdictions.

- The funds raised do not closely relate to actual usage, and excise levies are only approximately related to usage.

- There is no link between these various charges on vehicles and the costs of providing and maintaining our present road network.

- Road funding by governments is considered to be an essentially political arrangement, inherently arbitrary and inefficient for both road users and network asset management.

- The projected funds generated by road and fuel charges are considered insufficient to fund the existing road network going forward and to meet future infrastructure needs.

What are the ideas for the future?

Heavy Vehicle operators under the current system pay the same annual cost whether they travel 1 million or 50,000 km in a year. The average cost of running a prime mover and trailer is approximately $750,000 annually, regardless of distance travelled. Options to address this inequality include mass distance charging which prices every tonne you move and how far you take it along which type of roads. The Government is assessing two options for a national mass distance charge system:

- a mass-distance-location charge variable by state or

- a mass-distance-location charge based on road type.

Neil Findlay Chair Queensland Transport and Logistics Council said

“The industry is not against the idea of mass distance charging, so long as the program is equitable, simple, transparent and the funding is designated to improve road infrastructure and increase supply chain productivity and safety.”

Mass distance charging is not a new idea. The concepts have been modelled and explored in numerous government reports over many years. Technology advances will improve the ability to record the distance travelled, the weight of the load and track which roads are being used. Collecting the data is common pace for big operators but what about the owner drivers or part time drivers. How simple and cost effective will it be for them to collect and manage data?

The recent launch of the National Heavy Vehicle Charging Pilot is a welcome next step in the reform process. The government will offer truck operators telematic devises to participate so they can identify how far loads are travelling on which roads where. The evidence this pilot will collect is critical to designing the right policy mix and operators are urged to get involved. If the government has no visibility of the industry as a whole the decisions made will not be for every one’s benefit. To participate contact the National Pilot team on 1800 065 113 or email National.Pilot@infrastructure.gov.au.

Collecting the evidence is the easier step. Developing the policy will be more difficult to navigate. Untangling the three layers of complex government revenue collection and spending is no easy task. Infrastructure spending is a political device politician’s like to use when voters are feeling unsteady. With good governance structures, a transparent process of allocating funds and a strong national vision a ‘Building Australia Fund’ option might deliver. The real question is in our current environment, that has become ever more challenging for far-sighted reform are political leaders are up to the task.

[1] Road Pricing and Provision – Changed Traffic Conditions Ahead, (2018) Australian National University Press

by Kim Kennedy | Nov 7, 2019 | Latest News

Queensland Transport and Logistics Council is very pleased to announce Dr Andrew Higgins appointment to the Board of Directors. Andrew will bring a national research perspective and a wealth of experience and knowledge of freight networks to the Board of QTLC.

Andrew is a Principal Research Scientist at CSIRO, based in Brisbane with core skills in operations research and transport optimisation. He has a long history of involvement in the freight industry, modelling and optimising complex industry and infrastructure systems, particularly with rail transport planning and logistics, agriculture supply chains, and intermodal transport. Developing TRAnsport Network Strategic Investment Tool (TRANSIT) for the CSIRO, which is a spatial model for simulating transport cost benefits from infrastructure investments (road upgrades, use of rail versus road, processing and storage facilities) and policy interventions in agriculture logistics.

We are all looking forward the valuable insights Andrew will bring to the organisation and the no doubt lively debate.

QTLC is primed and ready to take on new challenges and reach our goal of being the ‘go to’ independent freight and logistics advisory body for Queensland.

Chair Neil findlay

Andrew will join the team which currently includes, Chair Neil Findlay, Neil Scales, Peter Garske, Andrew Rankin, and Michelle Reynolds, for further details on Board members and QTLC.